Knowledge: The Great Northern Lights of 1859

February 9, 2010

At first, it doesn’t seem that September 3, 1859, was out of the ordinary in the northern United States. The New York Times‘ “News of the Day” lists quotidian happenings: that the “depredations of the Apache Indians” in Arizona Territory have become “almost uncurable” [sic]; that the city’s churches, closed for the summer, were starting to reopen slowly; that an unfortunate situation with a boiler at a downtown machine shop had left one dead and several flung about.

Between paragraphs about the apprehension of a “mean rascal” who had been fleecing young maidens and a recap of the current attitudes of commodity markets (cotton, molasses, crude turpentine, lime: flat; dry cod-fish, hops and hides: an uptick in demand) was this mention:

“There was another brilliant display of auroral light last night.”

The nation was in thrall. The early state of photography was no match for the heavenly displays, instead recorded by rhapsodic, purple prose by enthusiastic newspaperman worldwide. “Soon after sunset,” we’re told by another New York Times article from the same day, “the streamers which mark every appearance of the Aurora were visible in the north. As the twilight deepened, the ‘merry dancers’ ventured from their hiding places and played along the horizon as though successive sheets of impalpable flame were sweeping over the sky.” The description continues for several hundred (almost intolerably florid) words and echo eyewitness accounts from Boston, Philadelphia, London—even as far south as the Caribbean.

At that moment in the evening of September 2, 1859, nearly two-thirds of the globe was enshrouded in vivid aurora, the earth’s magnetic field vibrating as if our planet were a clapper inside an immense electro-magnetic bell. In New England, residents could read books without a candle at one in the morning. In the Rocky Mountains it was reported that confused miners woke and began frying up breakfast, believing that daylight had arrived.

The outward reaction was a mix of Victorian confidence and fascination as scientists and self-elected experts tried to explain what was going on. A writer for the Times poked towards something solid when he explained that the “most popular theory attributes [the auroral display] to electricity,” but goes on to refute the notion, remarking that “that agent has been made responsible for everything which men did not know how to account for otherwise.”

Brooklyn Heights resident/authority/insane person E. Merriam submitted two long letters to the editor about the probable causes of the sparkling events. The Northern Lights, he claims, are “composed of threads like the silken warp of a web.” Sometimes, he says, these gossamer cosmic threads snap or shatter and fall down. They “possess an exquisite softness and a silvery lustre…I once obtained a small piece which I preserved.”

Merriam was also kind enough to explain to us that the air during auroral events was “invigorating” when inhaled.

While Americans wrote really bad prose and sailors spoke of skies like blood, across the Atlantic in England, astronomer Richard Christopher Carrington had been lucked into a miraculous vantage point—on the morning of the 1st, he watched the sun explode.

Carrington was a quintessential 19th century man of science, a showcase of Victorian ingenuity at a time during which no box had yet been built inside of which to think. His sun observation equipment was both elegant and homebrew: a brass telescope in his own luxurious dome, carefully calibrated filaments of wire dividing his captured images of sun into a rigorous grid.

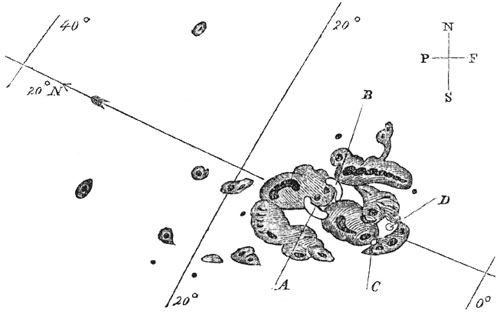

He was already antsy and ‘flurried’ because of the recent appearance of a substantial sunspot complex. His work that morning was to sketch the evolving spots for posterity. But suddenly, two brilliant points of light appeared in the midst of the sunspots, morphing into two kidney shaped masses of searing brightness. The sun’s actual brightness doubled temporarily in those areas. For an hour or so he recorded their every movement, realizing that he was seeing something that may never have been seen before. At the same time he was observing the emergence of the white kidneys, the earth was bonked resoundingly, if briefly, by a shock of solar energy.

Astronomer Richard C. Carrington's detailed diagrams of sunspot and flare activity on Sept. 1, 1859. "A" and "B" denote the white, kidney-shaped lights he saw.

It’s likely that these two earth-sized white blips were immense coronal mass ejections (CMEs). It’s also possible that they raced towards earth faster than usual because the “way had been cleared” by another CME, probably just days before. At this point the world had already been experiencing awesome auroral displays for several days, indicating a continuing cosmic storm. Instead of taking three or four days to get here, the massive flares walloped into earth after less than 18 hours.

Once the brunt of Carrington’s flare reached the earth, magnetic instruments worldwide started jittering frantically and didn’t stop for days. The earth’s magnetic field undulated. In New England and Canada, telegraph operators weary of massive interference finally gave up, unplugged their batteries, and ran their communications using only the wild currents in the earth around them. This worked, just fine, for hours.

Carrington was wary about presenting his observations to scientific authorities and societies, worried about flying in the face of conventional wisdom, which held that no explosion on the sun could possibly be big enough to affect earth. He got lucky when Richard Hodgson, Esq. of Highgate, stepped forward and claimed to have corroborating observations. Both spoke at a Royal Society event that November, resulting in general acceptance of the relevance of their solar observations to the enormous magnetic storm seen here on earth.

This was the biggest solar magnetic event in recorded history, on a magnitude that usually only happens about once every 500 years. What would happen if this were to happen now? In short, a lot. Certainly not Armageddon, but our communications systems and satellites and radios and whatnot would need a goodly amount of TLC and dollars afterward.

Sources

This is the first post I’ve written on Lyza.com that involved accessing actual databases at actual research institutions, including JSTOR and ScienceDirect, via the Multnomah County Library and Portland State University, respectively. Exciting!

- Stuart Clark, Astronomical fire: Richard Carrington and the solar flare of 1859, Endeavour, Volume 31, Issue 3, September 2007, Pages 104-109, ISSN 0160-9327, DOI: 10.1016/j.endeavour.2007.07.004.

(http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6V81-4PJ6BF9-1/2/fc4386a02418a60649b5696254570017) - http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=timeline-the-1859-solar-superstorm

- Balfour Stewart, On the Great Magnetic Disturbance of August 28 to September 7, 1859, as Recorded by Photography at the Kew, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 11, (1860 – 1862), pp. 407-410

- NEWS OF THE DAY

New York Times (1857-1922). New York, N.Y.:Aug 30, 1859. p. 4 (1 pp.) - THE AURORA BOREALIS. :THE BRILLIANT DISPLAY ON SUNDAY NIGHT. PHENOMENA CONNECTED WITH THE EVENT. Mr. Meriam’s Observations on the Aurora–E. M. Picks Up a Piece of the Auroral Light. The Aurora as Seen Elsewhere–Remarkable Electrical Effects.

New York Times (1857-1922). New York, N.Y.:Aug 30, 1859. p. 1 (1 pp.) - AURORA AUSTRALIS. :Magnificent Display on Friday Morning. Mr. Merlam’s Opinions on the Bareul Light–One of his Friends Finds a Place of the Aurora on his Lion-corp. The Aurural Display in Boston. New York Times (1857-1922). New York, N.Y.:Sep 3, 1859. p. 4 (1 pp.)

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aurora_%28astronomy%29

- NASA: NASA Scientist Dives into Perfect Space Storm

2 Comments

Recently Reviewed

Get the Books

Read my Reviews

Related Posts

- Knowledge: Getting everyone on the same page…of the calendar

January 15, 2010 - Planets Everywhere: Building our model solar system

April 1, 2010 - Knowledge: Earthshine and the moon’s full earth

February 24, 2010 - Knowledge: Tides

January 26, 2010 - Knowledge: The year the trees stopped counting

January 20, 2010

this is utterly fascinating. i had never heard the least thing about it. i’m sort of sorry i can’t buy a piece of the broken sky…

This is so good on so many levels. You were born to write like this.